“If you do not have needs, you once did.” ~ Marshall Rosenberg

When I was born, my mother did not want me. In the northern part of India, there is still a very strong preference for having a male child. A female child is often seen as a burden because of the social and economic traditions of patriarchy.

Because of this initial rejection, I became highly sensitive to my parents’ inner worlds. In my deep longing to be loved and accepted, I mastered the subtle art of sensing their needs and feelings, becoming a natural caretaker.

I would come back …

“If you do not have needs, you once did.” ~ Marshall Rosenberg

When I was born, my mother did not want me. In the northern part of India, there is still a very strong preference for having a male child. A female child is often seen as a burden because of the social and economic traditions of patriarchy.

Because of this initial rejection, I became highly sensitive to my parents’ inner worlds. In my deep longing to be loved and accepted, I mastered the subtle art of sensing their needs and feelings, becoming a natural caretaker.

I would come back from school and notice my mother’s overwhelmed face. Her days were always busy and full with myriad responsibilities. Before I knew it, I slid into the role of mothering my younger brother. And so, growing up, due to circumstances and adaptation, my favorite thing in the world became making someone feel at home.

In my twenties, designing emotionally safe spaces became the core of my work. First as a university teacher and eventually as a wellness coach, I became a professional caretaker. Along with my students, I experienced the deepest textures of fulfillment and intimacy at work. My work became a nest for rebirthing and nurturing. Non-judgment, emotional safety, and warmth were its key tenets. It was an experience of inclusion, ease, and belongingness.

One day, I faced the decision to let go of a student who had been emotionally aggressive toward me. I felt fragmented into parts: one part feeling hurt for myself, and the other part feeling care and protectiveness toward the student who had crossed the line. In all honesty, I was more attuned and identified with the latter part.

For days, I suffered. I tried to find a way for these parts to coexist, but they couldn’t. I had to face the emotional reality of chaos and discomfort. As they say, if it is hysterical, it must be historical; during this internal churning, I had a significant insight. I realized that my favorite thing originated from my least favorite thing in the world.

I never wanted to subject anyone to the experience of feeling emotionally walled out, rejected, homeless, and undesired. This tenderness, stemming from my early childhood experience, made me highly attuned to anyone who might feel similarly.

Ironically, in designing a non-hierarchical classroom and workplace where everyone shared power, I was not taking my own needs and feelings into account. I was not listening to my own needs and feelings. To quote the late American psychologist Marshall Rosenberg, “If you do not have needs, you once did.”

It awakened me to the awareness that I had learned to neglect my needs to the point where they did not matter as much as someone else’s. This was a learned behavior, an adaptation I made very early in my life.

This prevented me from drawing boundaries, even when necessary to protect my vitality and life spark. In trying to embody elements of an emotionally safe home, I was tuned out to my own personal truths, especially the subtle ones. It was through this experience of conflict that I could see the contest between these different parts.

In that moment of insight, my heart felt lighter after days of heaviness. I could see the beauty and dignity of my needs again. The part of me that did not receive unconditional acceptance from her primary caretakers had birthed the part that valued deep care and emotional safety for others. I was trying to soothe my grieving part by breathing life into others.

From a spiritual dimension, it was beautiful to witness that others were a part of me in this cosmic adaptation. However, in this material realm, it was important to acknowledge separation as a prerequisite for co-existence.

My learning was to first breathe life into my own abandoned part, nurturing it back to richness, ease, and wholeness, and then share my gifts from that choiceful place.

Another simple question helped me: Every night, why do I lock the door of my apartment? It is to protect my space from strangers. Similarly, for me to embody emotional safety at my workplace, I need to first feel safe.

I saw the light and shadow meet at the horizon. Boundaries, which once seemed like rude, disruptive, and violent borders separating people, suddenly felt like love lines inside my body, helping me to love better, richer, and more honestly.

Learning to set boundaries was not easy. It required me to slow down and witness uncomfortable truths about my past and present. I had to learn to honestly understand where my giving was coming from and learn to heal and nurture my own grief.

It was only when I came in touch with that initial rupture that I could become more capable of giving genuine care and support to others without depleting myself.

This journey freed me from my savior syndrome and taught me to be self-compassionate and create a more authentic and nurturing environment for others.

Boundaries allowed me to reclaim my sense of self. They became a way for me to define what was acceptable and what was not, to express my limits, and to protect my emotional and mental health. This process also taught me the difference between passion and obsession.

Today, I am more attuned to my own needs and feelings. I understand that setting boundaries is an ongoing practice, not a one-time event. It involv

Related Posts

Recommended Story For You :

Discover the Obsession Method and Transform Your Relationships

Unveiling the Secrets to Rekindle Your Relationship and Get Your Girlfriend Back

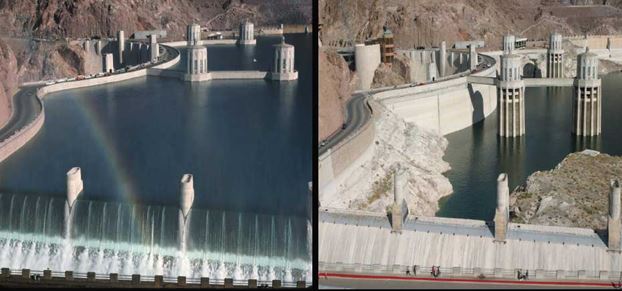

Unlocking the Secrets of Water Harvesters for Sustainable Solutions

Your Trusted Guide to Practical Medicine for Every Household

Discover the Obsession Formula for Magnetic Connections

Transforming a Connection into a Lasting Relationship with One Simple Move

The High Output Pocket Farm – Cultivating Life amidst Desert War Zones

EVERYTHING IS HAPPENING THE EXACT TIME AND IN THE EXACT ORDER