“Boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.” ~Prentis Hemphill

I was talking with a friend about some aspect of a challenging relationship (I don’t even remember what it was now), and she lovingly informed me that I needed better boundaries. I nodded in understanding, but later I realized that I didn’t really know what that meant. Like, what do better boundaries actually look like? And how does one go about developing them?

It’s all fine and dandy to know that “No” is a complete sentence, but how does that apply to a …

“Boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.” ~Prentis Hemphill

I was talking with a friend about some aspect of a challenging relationship (I don’t even remember what it was now), and she lovingly informed me that I needed better boundaries. I nodded in understanding, but later I realized that I didn’t really know what that meant. Like, what do better boundaries actually look like? And how does one go about developing them?

It’s all fine and dandy to know that “No” is a complete sentence, but how does that apply to a coworker just needing a quick hand (even though I’m already swamped)? Or a friend needing help with a minor crisis (but I’m not feeling so great)? Or a parent needing medical attention (when I’m really not qualified and still trying to get on my own two feet)? Or a new beau asking very reasonably to be accepted as they are (while my core needs aren’t getting met)?

I didn’t have the answers then, so I just filed that recommendation away, pending further intel. I had already moved halfway across the country to get some distance from both of my (divorced) parents, but I would eventually develop a more diverse toolkit of relational skills.

Flash-forward a year or two, and I was participating in some structured activities with a group of people who practiced “Authentic Relating” when I encountered what I later realized were healthy boundaries—for the first time in my life.

These beautiful souls would occasionally turn down an invitation (to an activity as part of the event or perhaps for something after) in the most disarming way I’d ever experienced: They would deliver a no without disconnecting. It was pleasant and friendly without being apologetic or abrasive. It was truthful, and it was immediately clear that it wasn’t personal. It felt surprisingly good, like honesty and mutual respect.

I realized that I felt safe to be upfront about my nos with them too, trusting that they would appreciate my authenticity (delivered responsibly) and not have their feelings hurt or try to twist my arm in their favor.

It also dawned on me that if these folks were so comfortable saying no, I could trust the sincerity of their yeses and not fall into my usual pattern of asking “Are you sure?”, worried that they were just being nice and would end up resenting me later. Wow! How freeing is that?!

Then I was confronted with my own question: What had I been doing all my life, trying to be “nice”? I was thoroughly inspired to enhance the quality of safety and trust in my own relationships. This opening led me to deeper and deeper insights about the nature and nuances of boundaries.

One of the next revelations on my journey was that our boundaries are essentially our resource limits, and then I found myself confronted by the whole “abundance vs. scarcity” thing. As a recovering people-pleaser, I already wanted to be able to say yes to everything, and having to say no to things felt even scarier with the story that a no could mean limiting myself and putting blocks between me and my dreams. I was supposed to be abundant, damn it, not limited!

As it turns out, there is a substantial difference between the mindset of abundance or scarcity and the reality of abundance and scarcity in the world.

There is certainly an abundance of life on this planet, but each one is fleeting. I may have the potential for financial abundance, but at any given moment, the amount of money I have is finite. One of the most fixed resources of all is time. There are only twenty-four hours in each day; in some cases, that might feel abundant, and in others, it might feel scarce.

Then I noticed that some of the most precious resources on earth, such as gold and diamonds, are valued in large part precisely because of their scarcity. Suddenly, my limited resources became precious to me. My time, money, energy, attention, and care were suddenly like jewels, and I was their honored steward.

The “oxygen mask rule” was now clearer to me: If we’re not good to ourselves, we’re no good to anyone else.

When we let our resources become depleted, we have nothing left for the people and causes we care most about; often, we even do them harm when we act out from the survival mode that being under-resourced triggers. In many cases, we end up blaming others for over-taking when we were the ones who were over-giving. (Resentment is almost always the byproduct of a failed boundary.)

Sometimes, we’ll even get preemptively resentful over being put in the position of having to say no—“How could you even ask me that?!” This happens because we’re holding onto misplaced responsibility for other people’s emotions. We completely lose sight of the option to simply say, “No, thank you.” “Nah, I’m good.” “Nope.” “Sorry, I can’t make it. Maybe next time!” “I can’t help you with that, but I might know someone who can.” “I’ve gotta go now. I love you, and I’ll call you tomorrow.”

But what if we don’t even know what our limits are?

What I came to discover next was just how deeply seated my fawning behavior was. There’s talk of “being a yes” to some things and “being a no” to others. It gets tricky, though, for those of us who grew up carrying the misplaced responsibility for other people’s emotional states so that we could feel safe, as this tends to develop a reflexive yes.

In the moment of a request (or even a perceived need), we are a yes, but it’s to the person—their acceptance of us and their ease. This yes arises before we even hear or process the request because we have an external orientation that makes other people’s acceptance of us (rather than our own) our source of security.

We are so quick to say yes to them because we just want to relieve them of their burden and avoid the terror of making them wait for us to consider whether we’re a yes to their actual request. Of course, this is all subconscious and so habitual that we’re not even aware that it’s driving us. It’s hard to notice if you’re a no to a request when you’re already a yes to the requester.

Once we become aware of this pattern, though, we start getting acquainted with our own limits, often for the first time, and then we start to realize how much power we’ve been abdicating.

On our quest to right the wrongs, most of us encounter the unfortunately prevalent notion that we have to sacrifice our compassion in order to become empowered. After letting our boundaries be trampled for so long, once we find our no, we start to wield it like a sword with the faulty assumption that our only options for boundaries are “flimsy fences” or “spiked walls,”

Yet, spiked walls are no healthier than flimsy fences. Both of these dysfunctional boundary styles lack the key ingredient of appropriate responsibility. When I finally took full ownership of my limits, there was no one to blame when they were exceeded but myself, and there was no need to be rude about them because they were in my power to care for.

Then I remembered a piece from my dog training years that was about following a no with a yes, and I combined it with the connected rejections I learned from the “authentic relaters” for a way to ease my fawning response while still being boundaried.

I started telling people, “I’m not available for that, but I am available for this.” A true no, followed by a true yes.

>> “I’m sorry, Barb; I can’t help you with that project right now. If you still need help tomorrow, I’ll have some time after lunch.”

>> “No, I can’t help you move today, Sam, but I might be able to help you unpack this weekend.”

>> “I’m not sure what those symptoms mean, Mom. Here’s an emergency nurse hotline—please give them a call.”

>> “You’re right, John. I do want to accept you as you are, so if my requests are outside of your capacity, then this is not going to be a healthy relationship for me, which means it won’t be good for either of us. I really appreciate you, though, and I’d like to stay friends if you’re open to that.”

These are “selective gates,” and there is no quick fix to getting there. We have to devote time and attention to the uncomfortable transition of rooting our security within ourselves so we have the foundation of self-love and self-acceptance to brave the fear of rejection that is always at risk when speaking our truth.

Selective gates are not only communicated through not-that-but-this. In our closest relationships, we can offer information about our limits and the consequences of them being exceeded as gifts for our loved ones to understand and support us better.

It’s important to understand that boundaries are not the same thing as needs. Because they are simply our limits, there’s nothing to request and only self-care to be applied.

As my foundation got stronger, I stopped asking for others to make adjustments and started simply informing them about what comes up for me under certain circumstances and what I needed to do as a result.

This model looks like: “When [X] happens, I feel [Y], and so to care for myself, I will [do Z].”

>> “When it’s early, my brain is not fully online, and I can get grumpy if prodded. You’re welcome to make contact and I will listen without responding, but if you ask me stuff before I’m fully awake, I’ll just grunt.”

>> “When we’re on our trip, if we want to do different things, rather than one of us getting disgruntled, I’ll just go my own way and meet back up with you after.”

>> “When I receive harsh criticism, I feel shame, and so to care for myself, I’ll remove myself from the conversation.”

I call this boundary style “selective gates” because we get to choose how people can have access to us, and they get to know the rules. And since these are defined by behaviors instead of whole people, folks have the option to use the gate or be on their way.

(Hot tip: These only work if you actually follow through on your end—and be consistent. Also, be prepared to restate your boundaries a few times. Feel free to have a limit there too, but I’d allow two or three repeats for the learning curve.)

In other cases, we might be a yes to a request, but it needs to be qualified. Here, we need to communicate our boundaries in a more proactive way, and it can be really simple—no lengthy explanations required. The winning strategy with these boils down to explicit clarity, with minimal room left for assumptions, misinterpretations, or “psychic” games.

Instead of an open-ended yes that is likely to leave us trampled, we can state our conditions outright.

>> “Sure, I’ve got five minutes.”

>> “No worries, just let me know by Wednesday.”

>> “I can do one of those things.”

Again, consistency is key. We’ve got to stick to our stated limits, or our words will lose their value.

Boundaries are a service! Others can be bummed by our nos or our conditions, but if they’re a counterpart in a quality relationship with us, they’ll also appreciate our honesty and self-care, for that is how we’re able to show up to the relationship resourced and how trust is built. Conversely, this insight can also help us accept a disappointing no from someone else and truly respect their boundary at the same time.

Love is unconditional, relationships are not; that’s what boundaries are for.

Having a big heart is not the problem. Please don’t wall yours off—just mend your fences and install gates. There’s no need to sacrifice your compassion in order to become empowered. Empower your compassion so it’s big enough for yourself as well as others.

What has worked wonders for me is a regular practice of study, self-reflection, embodiment, interactions, and support. I call it my “peaceful power practice,” and it involves a lot of reading and educational programs, little inspographics that I create and keep on my phone as touchstone reminders, frequently journaling and reviewing my entries, habitual introspection, regular chakra meditations, mindfulness in my connections with fellow humans (especially when triggers are involved), and a core network of trusted people.

Developing better boundaries has been a challenging road, but it continues to be a deeply rewarding one.

About Mariya Graestone

Mariya Graestone, aka Love Coach Mariya, lives in Austin, TX, and coaches women around the world on developing healthy boundaries, nurturing self-love, and breaking cycles of difficult relationships.

Get in the conversation! Click here to leave a comment on the site.

Related Posts

Recommended Story For You :

Discover the Obsession Method and Transform Your Relationships

Unveiling the Secrets to Rekindle Your Relationship and Get Your Girlfriend Back

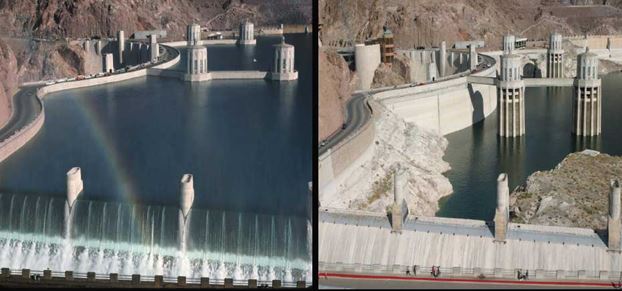

Unlocking the Secrets of Water Harvesters for Sustainable Solutions

Your Trusted Guide to Practical Medicine for Every Household

Discover the Obsession Formula for Magnetic Connections

Transforming a Connection into a Lasting Relationship with One Simple Move

The High Output Pocket Farm – Cultivating Life amidst Desert War Zones

EVERYTHING IS HAPPENING THE EXACT TIME AND IN THE EXACT ORDER